Part 5: Death Marches, Liberation and Displaced Persons Camps (1944-1957)

Survivors of the death march from the Dachau concentration camp were liberated by American troops when SS guards retreated in late April and early May 1945. Photo credit: Yad Vashem #3845/1

After several major military defeats, and in an desperate effort to conceal their crimes, Nazi Germany began the process of evacuating concentration and extermination camps during the winter and spring of 1945. The Nazis forced hundreds of thousands of prisoners on marches over long distances with little rest, food, or warm clothing. These evacuations came to be known as “death marches,” since those who could not keep pace were frequently shot or died of exhaustion. Prisoners from camps in western Poland were forced to march back to the German homeland, while other death marches attempted to move prisoners from one camp to another via trains (referred to as “death trains”). Approximately 250,000 prisoners perished in this final phase of Nazi terror.

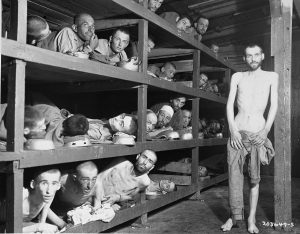

Former prisoners of the “little camp” in the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany stare out from the wooden bunks in which they slept three to a “bed.” Elie Wiesel is pictured in the second row of bunks, seventh from the left, next to the vertical beam, April 16, 1945. Photo credit: USHMM #74607

As Allied troops (American, British, and Soviet forces) began liberating the continent of Europe, they encountered—firsthand—the cruelty of the Nazi concentration camp system. Majdanek was the first extermination camp discovered by Soviet forces in July 1944, who also freed prisoners at Auschwitz-Birkenau in January 1945. American and British forces liberated the German camps of Dachau, Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen and hundreds of others later that spring. There, Allied troops discovered emaciated prisoners in severely overcrowded conditions, with rampant disease and starvation.

Horrific sights of human degradation and death shocked the soldiers. Piles of corpses were stacked high, while the bodies of living prisoners were skeletal and emaciated. Allied soldiers gave meals to the hungry prisoners, but many were too weak to digest food and died within days of being freed. In Bergen-Belsen, nearly 14,000 inmates perished after liberation despite the rescue efforts of the British military and Red Cross.

After Nazi Germany’s surrender in May 1945, Allied authorities and the United Nations (UN) organized hundreds of Displaced Persons camps (DP camps) to care for the approximately 7 million former prisoners and slave laborers who were now free, but homeless, jobless, and penniless. The UN and other humanitarian organizations tried to reunite lost survivors with their relatives, while the newly liberated prisoners attempted to rebuild their lives and form new families. The DP camps offered survivors a wide range of cultural and religious activities, where ethnic communities organized their own vocational schools, synagogues, churches, newspapers, theaters, and recreational activities.

Children at play in the Bindermichl displaced persons (DP) camp in Linz, Austria, 1947. Photo credit: USHMM #11850

More than 250,000 Jews lived in the network of DP camps between 1945 and as late as 1957. Many Jewish homes had been “Aryanized,” or taken over by their Christian neighbors, during the war. Jewish survivors also struggled with living in a place where they had experienced great trauma, and where they still felt hated, as antisemitism remained prevalent across much of postwar Europe. Instead, many Jewish people chose to immigrate to the United States or Israel, while smaller numbers settled in other countries, including Canada, Australia, South America, and South Africa in the late 1940s.

Poles, Ukrainians, Romanians, Hungarians, Belorussians, Czechs, and many other non-Jewish survivors from Central and Eastern Europe were repatriated to their countries of origin, but nearly 1 million people remained displaced for years after the end of World War II. Most of these Central and Eastern Europeans were reluctant to return to their home countries, which now were under communist rule and experienced Soviet oppression. The exception are Roma and Sinti survivors who were frequently left without support, and to this day, continue to experience widespread prejudice and economic discrimination in their daily lives.