Part 4A: Forced Labor Camps

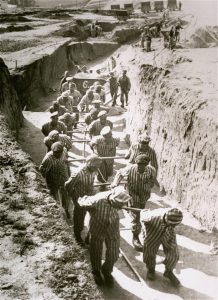

Forced laborers hauling cartloads of earth for the construction of the “Russian camp” at the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, April-May 1942. Photo credit: USHMM #12352

Forced labor was one of the central components of Nazi occupation. Millions of prisoners were required—against their will—to work for the Third Reich’s war effort, and frequently left to starve in order to ensure that Germans could eat. For the Nazis, the people living in occupied territories only mattered if they served Germany’s interests and strengthened the country’s military might. To this end, Himmler cruelly pointed out, “Whether 10,000 Russian women collapse from exhaustion while digging an antitank ditch only interests me insofar as the antitank ditch is dug for Germany.”

Nazi Germany conscripted civilians living in occupied territories to fill its labor shortage during World War II, and created approximately 35,000 forced labor camps in order to help the Nazi war machine. The majority of workers were Poles and Slavs, but included people from across Europe. Altogether, some 12 million people from 20 countries were deported to Germany and forced to work in farms and factories to replace Germans fighting at the front. Meanwhile, the SS oversaw construction of hundreds of satellite and subcamps that were used specifically for war-related needs. Many German companies, including Siemens and BMW, used and profited from forced labor.

Jewish forced laborers from the Mogilev ghetto on the way to work in Belarus, 1941. Photo credit: Yad Vashem #3955/360

Many of the entrances to the most infamous camps had signage bearing the phrase, “Arbeit Macht Frei” (“Work Shall Set You Free”), emblazoned overhead. The Nazis used this as a cynical ploy to give prisoners hope even though they were often intentionally and literally worked to death—a practice known as “annihilation through work.” At some extermination camps, however, the ability to work temporarily increased a prisoner’s chances of survival. Inmates also underwent regular examinations by Nazi doctors. Prisoners who were considered too old, sick, or otherwise unfit for work were executed. Many of these same physicians were also involved in the murder of psychiatric patients.