Timeline

This timeline provides a history of life in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and across the larger Plateau Vivarais-Lignon. It also briefly covers the history of Huguenots and other French Protestants. It focuses particularly on the Holocaust years, during which nearly 5,000 refugees found shelter among the roughly 5,000 farmers and villagers who lived there.

Le Chambon & The Plight of French Protestants in the 17th and 18th Centuries

Le Chambon-sur-Lignon is a village of about 2,800 inhabitants on the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon, 75 miles south of Lyon, nestled in the western foothills of the French Alps. Its environs, often called the Plateau, had been a place of refuge for French Protestants escaping Catholic persecution since before King Henry IV signed the Edict of Nantes in 1598. This decree granted the Calvinist Protestants of France (also known as Huguenots) significant rights for the first time. Within a year of its signing, the first churches on the Plateau were built in what is today Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and Le Mazet-Saint-Voy, three miles away.

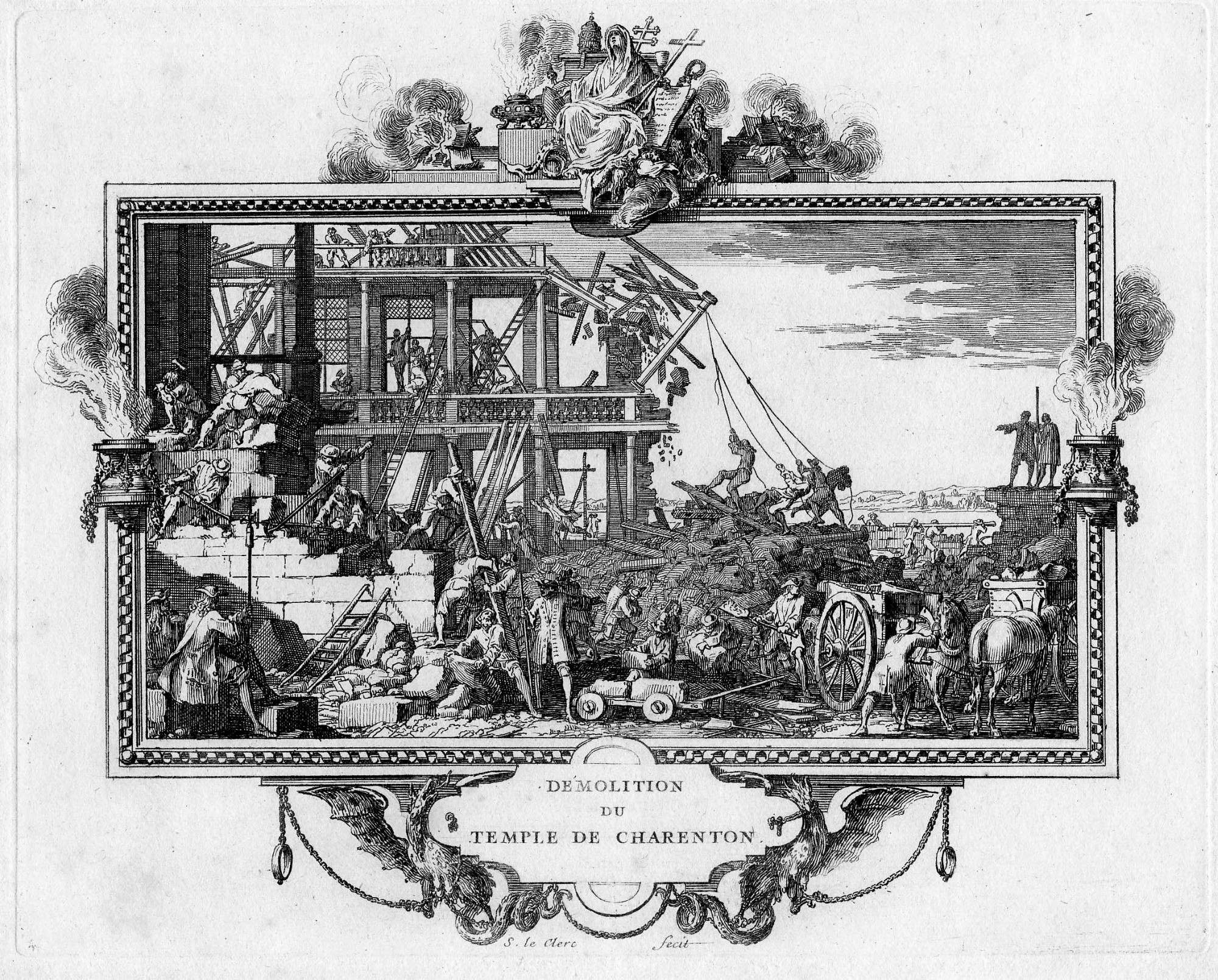

Their lives became tenuous once more beginning in the mid-17th century, when King Louis XIV embarked on a plan to kill or convert all French Protestants to Catholicism. This period of intolerance culminated in the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, again stripping Protestants of their rights.

After that, Protestants hid and congregated in remote areas to worship. The geographic isolation and inaccessibility of the Plateau made it an ideal refuge for Huguenots. The mountains around Le Chambon became one of the places in le Désert (the Desert), the term used for the period and places of worship when Protestantism was forbidden from 1685 to 1787. Preachers were subject to the death penalty and followers risked slave labor during this time.

Le Chambon & The Plight of French Protestants in the 17th and 18th Centuries

1598-1787

Le Chambon-sur-Lignon is a village of about 2,800 inhabitants on the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon, 75 miles south of Lyon, nestled in the western foothills of the French Alps. Its environs, often called the Plateau, had been a place of refuge for French Protestants escaping Catholic persecution since before King Henry IV signed the Edict of Nantes in 1598. This decree granted the Calvinist Protestants of France (also known as Huguenots) significant rights for the first time. Within a year of its signing, the first churches on the Plateau were built in what is today Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and Le Mazet-Saint-Voy, three miles away.

Their lives became tenuous once more beginning in the mid-17th century, when King Louis XIV embarked on a plan to kill or convert all French Protestants to Catholicism. This period of intolerance culminated in the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, again stripping Protestants of their rights.

After that, Protestants hid and congregated in remote areas to worship. The geographic isolation and inaccessibility of the Plateau made it an ideal refuge for Huguenots. The mountains around Le Chambon became one of the places in le Désert (the Desert), the term used for the period and places of worship when Protestantism was forbidden from 1685 to 1787. Preachers were subject to the death penalty and followers risked slave labor during this time.

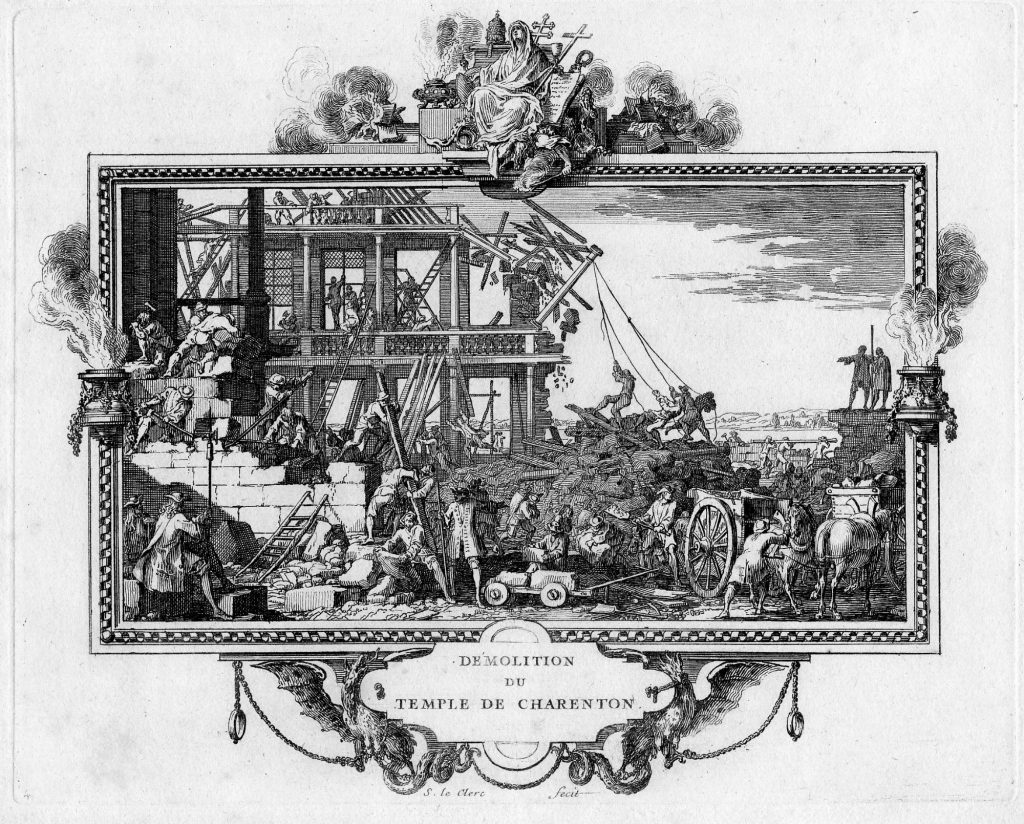

Image: The destruction of the Protestant church of Charente in ParisCredit: Société Historique du Protestantisme Français

A Healthy Escape: Le Chambon as a Refuge from Urbanization and Industrialization

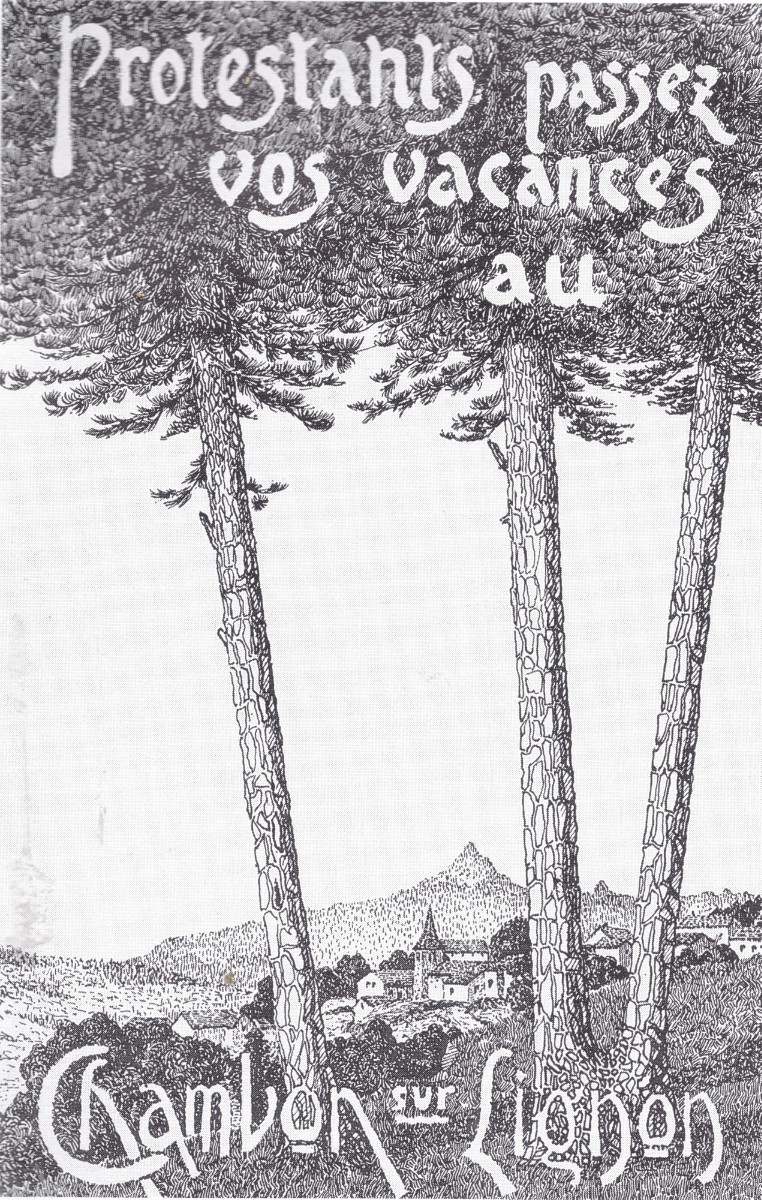

In the decades leading up to World War II, Le Chambon and the surrounding Plateau became an ideal setting for social Christianity and middle-class tourism. With clean air and beautiful scenery, it offered an alternative setting from the rapid industrialization and urbanization taking place in France.

As early as 1893, Pastor Louis Comte of the nearby city of Saint-Étienne arranged for miners’ children to vacation on the Plateau during the summer. This became the Œuvre des Enfants à la Montagne (Children’s Mountain Charity), hosting children from beyond the Saint-Étienne area, including southern France and Algeria. By 1914, there were children’s homes throughout the Plateau.

Fresh air tourism also increased throughout the Plateau, aided by the opening of a train line as well as a tourist office in 1902 and 1912, respectively.

A Healthy Escape: Le Chambon as a Refuge from Urbanization and Industrialization

1893-1914

In the decades leading up to World War II, Le Chambon and the surrounding Plateau became an ideal setting for social Christianity and middle-class tourism. With clean air and beautiful scenery, it offered an alternative setting from the rapid industrialization and urbanization taking place in France.

As early as 1893, Pastor Louis Comte of the nearby city of Saint-Étienne arranged for miners’ children to vacation on the Plateau during the summer. This became the Œuvre des Enfants à la Montagne (Children’s Mountain Charity), hosting children from beyond the Saint-Étienne area, including southern France and Algeria. By 1914, there were children’s homes throughout the Plateau.

Fresh air tourism also increased throughout the Plateau, aided by the opening of a train line as well as a tourist office in 1902 and 1912, respectively.

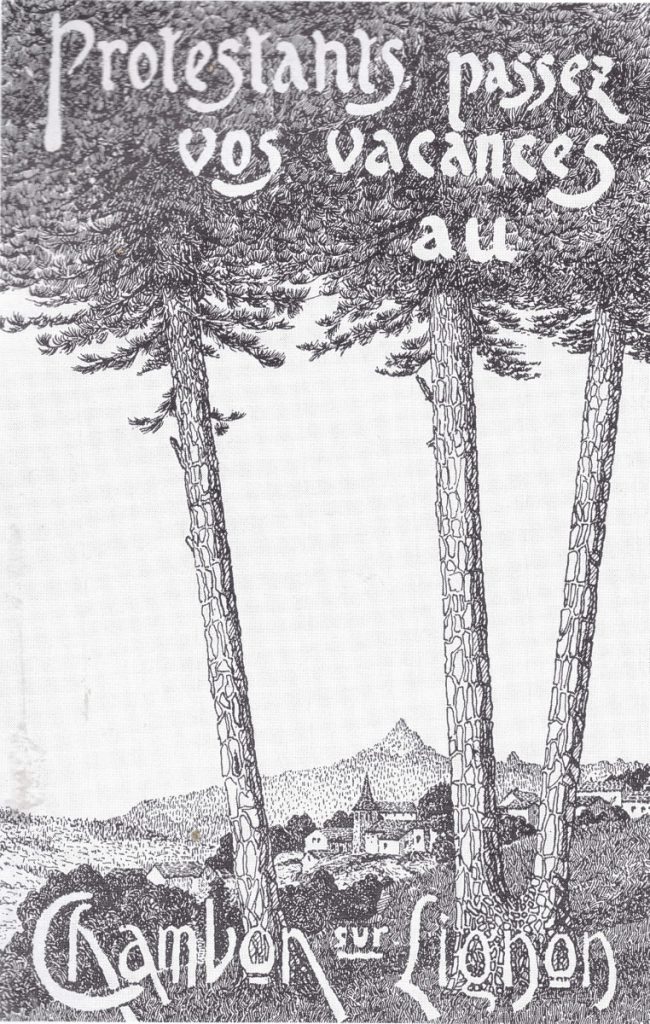

Image: An advertisement made by Mayor Charles Guillon encouraging Protestants to vacation in Le Chambon

Credit: Commune du Chambon-sur-Lignon

New Leaders in Le Chambon

In response to excesses of economic liberalism and industrialization, social Christianity combined Christianity and socialism to fight poverty among the working class. Charles Guillon, Le Chambon’s pastor and mayor at the time, hosted the 6th Congress of the French Federation of Social Christianity in 1933. A dairy cooperative founded in 1930 exemplified social Christianity on the Plateau.

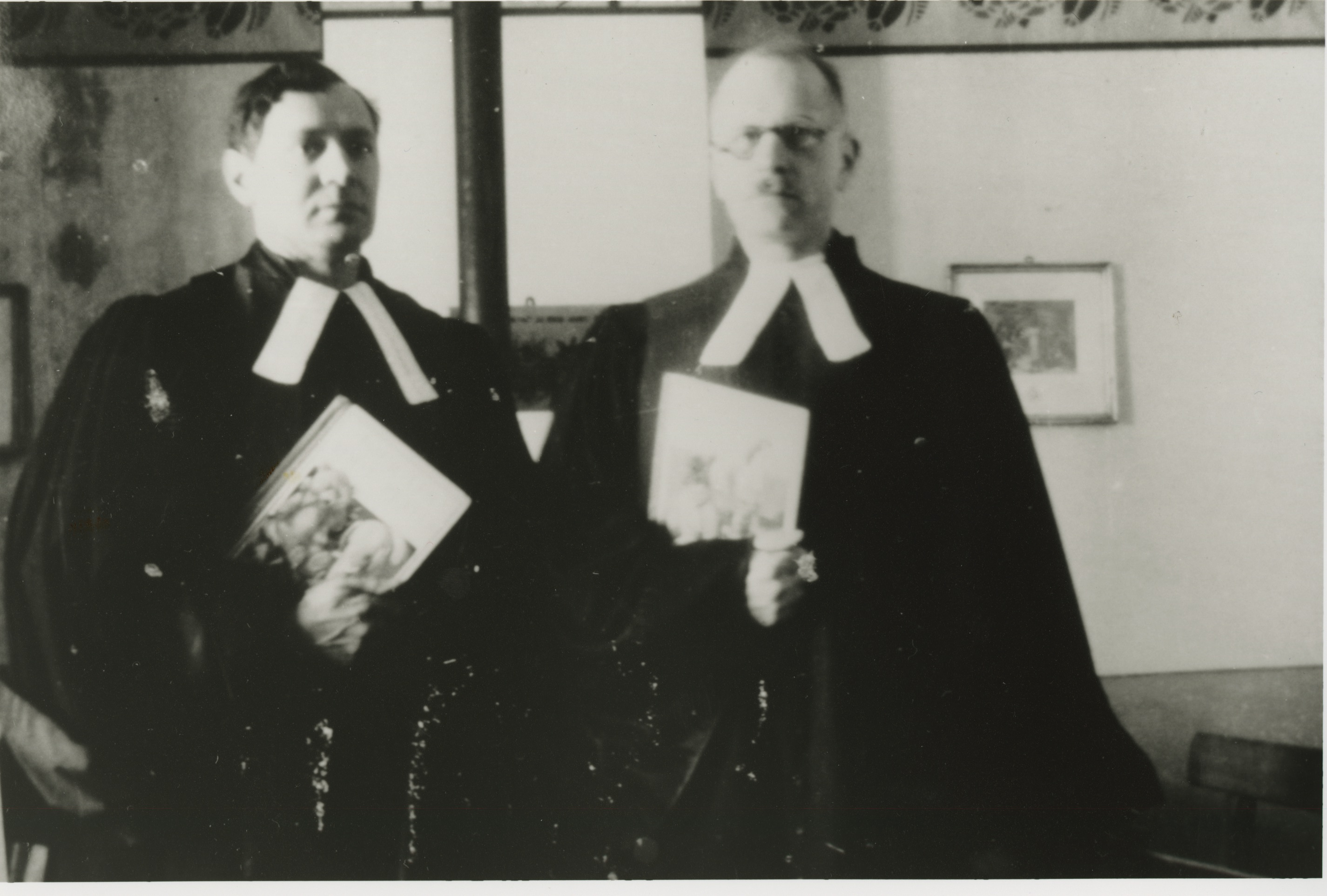

In 1934, the arrival of a radical new pastor, whose pacifism and conscientious objection had been profoundly affected by World War I, accelerated the transformation of Le Chambon from a town of ideals to a town of action. Pastor André Trocmé had been rejected by more cosmopolitan parishes because of his politics: with a German mother and an Italian wife, and as a former New York City resident, Trocmé was quite worldly for the times and was therefore viewed with some suspicion. In 1938, Trocmé and his co-pastor, Édouard Theis, founded École Nouvelle Cévenole (the New Cévenole School) in Le Chambon, a private co-ed Protestant school, which was revolutionary at the time.

New Leaders in Le Chambon

1930-1934

In response to excesses of economic liberalism and industrialization, social Christianity combined Christianity and socialism to fight poverty among the working class. Charles Guillon, Le Chambon’s pastor and mayor at the time, hosted the 6th Congress of the French Federation of Social Christianity in 1933. A dairy cooperative founded in 1930 exemplified social Christianity on the Plateau.

In 1934, the arrival of a radical new pastor, whose pacifism and conscientious objection had been profoundly affected by World War I, accelerated the transformation of Le Chambon from a town of ideals to a town of action. Pastor André Trocmé had been rejected by more cosmopolitan parishes because of his politics: with a German mother and an Italian wife, and as a former New York City resident, Trocmé was quite worldly for the times and was therefore viewed with some suspicion. In 1938, Trocmé and his co-pastor, Édouard Theis, founded École Nouvelle Cévenole (the New Cévenole School) in Le Chambon, a private co-ed Protestant school, which was revolutionary at the time.

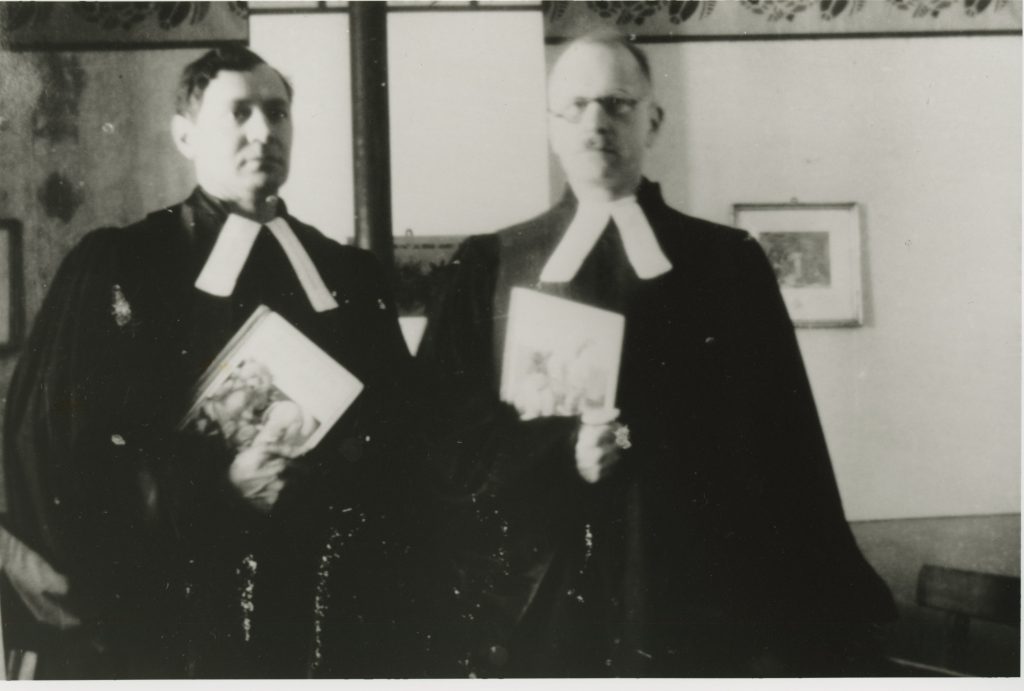

Image: Pastors André Trocmé and Édouard Theis, circa 1940Credit: André Trocmé and Magda Trocmé Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection

Spiritual Resistance in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon

Spiritual resistance, one of the hallmark tenets preached by Le Chambon’s pastors, was a guiding force for the town’s citizens, who collectively sheltered thousands of refugees from Spanish, French, and Nazi oppression. Trocmé drew inspiration from the Calvinist tradition of humanism, as well as other sects, including the American Quakers, whom Trocmé greatly admired for their active, tireless pursuit of alleviating human suffering—including in the internment camps of southern France.

Trocmé’s resolve to preach spiritual resistance would soon be tested. On June 17, 1940, a month after Nazi Germany invaded France through its borders with Belgium and Luxembourg, the displaced French parliament anointed Marshal Henri-Philippe Pétain as Chief of State.

On June 22, 1940, French and German generals signed an armistice granting a collaborationist French government autonomy throughout the southeastern two-fifths of France (the Free Zone—which included Le Chambon), while the Nazis controlled the northern and western three-fifths (the Occupied Zone). From the new capital in Vichy, the government changed the nation’s motto from “Liberty-Equality- Fraternity” to “Work-Family-Homeland,” echoing Nazism’s nationalistic ideology. The next day, June 23, 1940, was a Sunday. Pastors Trocmé and Theis addressed their parishioners in Le Chambon with the following words:

We face powerful heathen pressures on ourselves and our families, pressures to force us to cave in to this totalitarian ideology. If this ideology cannot immediately subjugate our souls, it will try, at the very least, to make us cave in with our bodies. The duty of Christians is to resist the violence directed at our consciences with the weapons of the spirit…

We will resist when our enemies demand that we act in ways that go against the teachings of the Gospel. We will resist without fear, without pride, and without hatred.

Trocmé’s sermon was the beginning of a larger movement that was joined by pastors in a dozen neighboring villages.

Spiritual Resistance in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon

June 23, 1940

Spiritual resistance, one of the hallmark tenets preached by Le Chambon’s pastors, was a guiding force for the town’s citizens, who collectively sheltered thousands of refugees from Spanish, French, and Nazi oppression. Trocmé drew inspiration from the Calvinist tradition of humanism, as well as other sects, including the American Quakers, whom Trocmé greatly admired for their active, tireless pursuit of alleviating human suffering—including in the internment camps of southern France.

Trocmé’s resolve to preach spiritual resistance would soon be tested. On June 17, 1940, a month after Nazi Germany invaded France through its borders with Belgium and Luxembourg, the displaced French parliament anointed Marshal Henri-Philippe Pétain as Chief of State.

On June 22, 1940, French and German generals signed an armistice granting a collaborationist French government autonomy throughout the southeastern two-fifths of France (the Free Zone—which included Le Chambon), while the Nazis controlled the northern and western three-fifths (the Occupied Zone). From the new capital in Vichy, the government changed the nation’s motto from “Liberty-Equality- Fraternity” to “Work-Family-Homeland,” echoing Nazism’s nationalistic ideology. The next day, June 23, 1940, was a Sunday. Pastors Trocmé and Theis addressed their parishioners in Le Chambon with the following words:

We face powerful heathen pressures on ourselves and our families, pressures to force us to cave in to this totalitarian ideology. If this ideology cannot immediately subjugate our souls, it will try, at the very least, to make us cave in with our bodies. The duty of Christians is to resist the violence directed at our consciences with the weapons of the spirit…

We will resist when our enemies demand that we act in ways that go against the teachings of the Gospel. We will resist without fear, without pride, and without hatred.

Trocmé’s sermon was the beginning of a larger movement that was joined by pastors in a dozen neighboring villages.

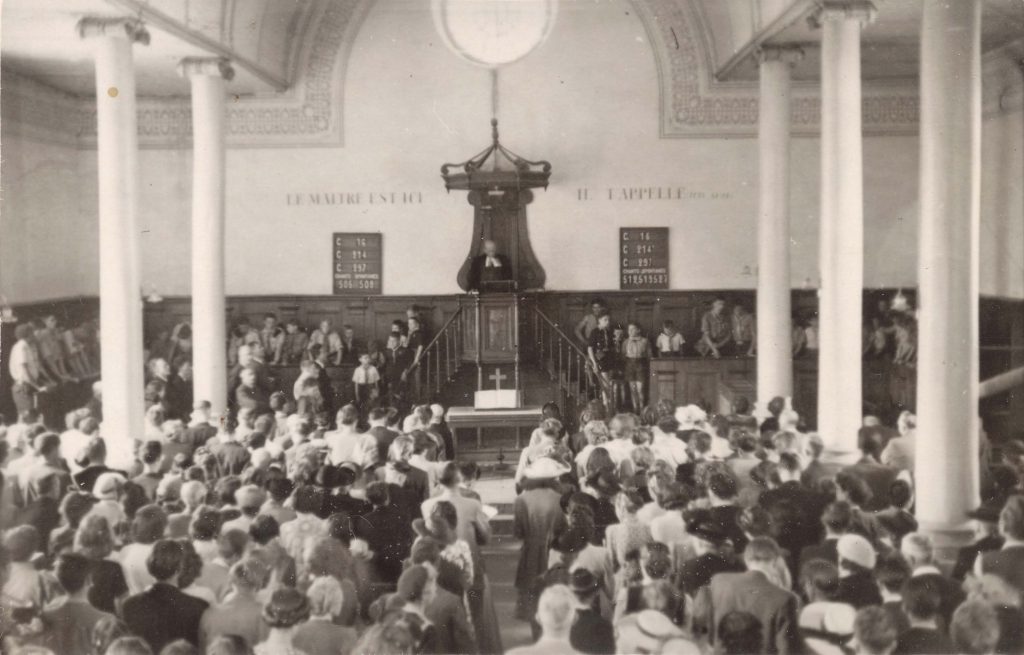

Image: Pastor Trocmé preaching inside the Protestant church of Le ChambonCredit: Fonds Darcissac/Commune du Chambon-sur-Lignon

Refugees Arrive at Le Chambon

The first refugees in Le Chambon were Spanish republicans fleeing Franco and the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s. Following the passage of anti-Jewish laws, Jews began flooding into the area either because they had spent time there before the War or because they had heard that it was a safe place.

Additional refugees came from the French internment camps for Jews, such as Gurs, Rivesaltes and Les Milles. In some cases, the French police arrested Jews caught trying to cross the Demarcation Line into the Free Zone to get to Marseille, where there were still boats leaving Europe for America.

Refugees Arrive at Le Chambon

1936-1942

The first refugees in Le Chambon were Spanish republicans fleeing Franco and the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s. Following the passage of anti-Jewish laws, Jews began flooding into the area either because they had spent time there before the War or because they had heard that it was a safe place.

Additional refugees came from the French internment camps for Jews, such as Gurs, Rivesaltes and Les Milles. In some cases, the French police arrested Jews caught trying to cross the Demarcation Line into the Free Zone to get to Marseille, where there were still boats leaving Europe for America.

Image: The Kann family, interned in the Gurs concentration camp in southwest France. Renée Kann Silver is pictured on the far right.Credit: Private collection of Renée Kann Silver

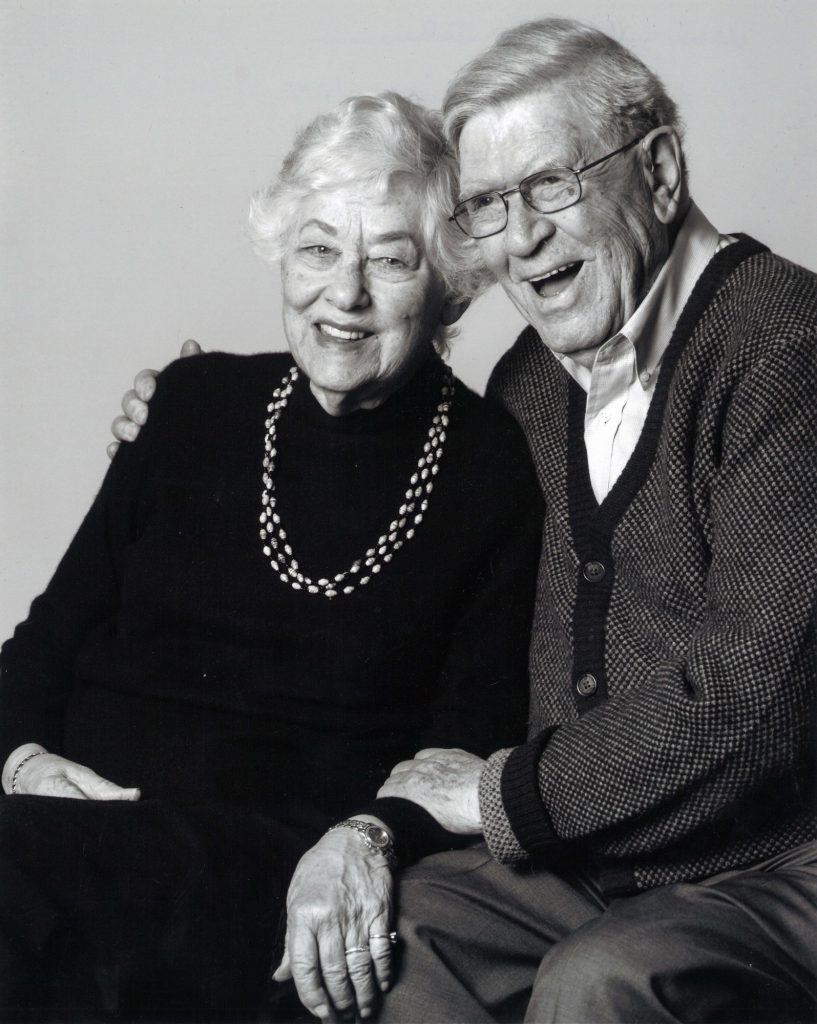

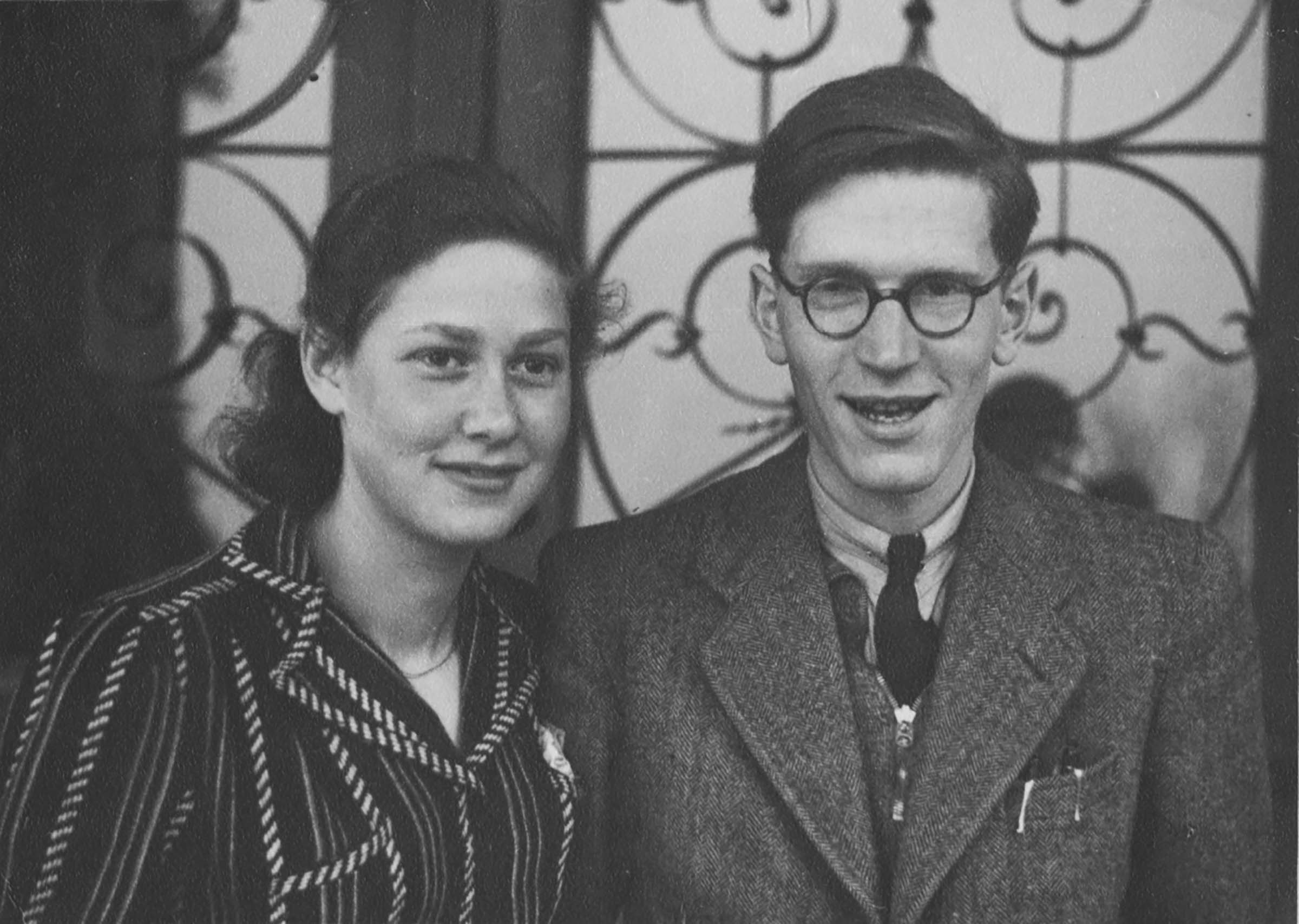

Hanne and Max Liebmann

On October 22, 1940, 6,504 Jews from the Baden, Palatinate, and Saar regions of Germany – including Kupferberg Holocaust Center speakers Hanne and Max Liebmann – were arrested, as part of Operation Bürckel, and deported to Gurs, a French-run concentration camp in the “free zone.” It was the only deportation from Germany that headed west to France instead of east to Poland.

Hanne and Max Liebmann

October 22, 1940

On October 22, 1940, 6,504 Jews from the Baden, Palatinate, and Saar regions of Germany – including Kupferberg Holocaust Center speakers Hanne and Max Liebmann – were arrested, as part of Operation Bürckel, and deported to Gurs, a French-run concentration camp in the “free zone.” It was the only deportation from Germany that headed west to France instead of east to Poland.

Image: Hanne and Max Liebmann in Switzerland after World War II

Credit: Private Collection of Hanne and Max Liebmann

Transporting Children to Safety

Several aid organizations—such as the Swiss Red Cross and the Cimade—were present inside the French camps and were able to transfer children, whose parents gave permission, outside the camps. Many parents knew this would be their children’s sole opportunity to escape the deprivations, hardships and unknown fate that lay ahead. Although they didn’t know it at the time, most of these children would never see their families again.

Representatives from aid organizations, such as Madeleine Barot, accompanied the children from the internment camps by train. For many of these children, their ultimate destination was Le Chambon.

On November 11, 1942, when the Nazis took over the whole of France, this avenue of escape to Le Chambon from the camps was closed.

For more information about Yad Vashem’s recognition of Madeleine Barot as Righteous Among the Nations, visit their website: Yad Vashem, The Righteous Among the Nations, Madeleine Barot

Transporting Children to Safety

1942

Several aid organizations—such as the Swiss Red Cross and the Cimade—were present inside the French camps and were able to transfer children, whose parents gave permission, outside the camps. Many parents knew this would be their children’s sole opportunity to escape the deprivations, hardships and unknown fate that lay ahead. Although they didn’t know it at the time, most of these children would never see their families again.

Representatives from aid organizations, such as Madeleine Barot, accompanied the children from the internment camps by train. For many of these children, their ultimate destination was Le Chambon.

On November 11, 1942, when the Nazis took over the whole of France, this avenue of escape to Le Chambon from the camps was closed.

For more information about Yad Vashem’s recognition of Madeleine Barot as Righteous Among the Nations, visit their website: Yad Vashem, The Righteous Among the Nations, Madeleine Barot

Image: Madeleine Barot, the founder of the Cimade, an aid organizationCredit: Cimade Archives

Passing the War Years on the Plateau

The rescue at Le Chambon and across the Plateau was sufficiently organized to place refugees—regardless of their circumstances. Children who arrived alone were put into special homes such as La Guespy, L’Abric, and Les Grillons, depending on their age; older students stayed in the Maison des Roches (House of Rocks); and farmers occasionally accommodated individual children, but mostly sheltered families.

As a rural, agrarian area, the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon was self-sustaining even during the deprivations of the war. Although hunger was widespread, there was always enough food to get by. Most children attended either the local public school run by Roger Darcissac, or The New Cévenole School. Young adults went to farm and trade schools. During free time, various activities were organized. Winter sports were very popular, especially because of the long winter. In the summer, the children played an assortment of sports and swam in the Lignon River.

While Jews were relatively safe in the villages, the gendarmes (armed police) attempted periodic raids. August Bohny, the head of the Swiss Red Cross in Le Chambon, once sent the gendarmes away claiming that they were on Swiss property, forcing them to return to Le Puy-en-Velay to verify the claim. Bohny thus had time to send the Jewish children into the forest. When the gendarmes returned, there were only Protestant children in the homes, and the police left without making arrests.

Passing the War Years on the Plateau

1940-1944

The rescue at Le Chambon and across the Plateau was sufficiently organized to place refugees—regardless of their circumstances. Children who arrived alone were put into special homes such as La Guespy, L’Abric, and Les Grillons, depending on their age; older students stayed in the Maison des Roches (House of Rocks); and farmers occasionally accommodated individual children, but mostly sheltered families.

As a rural, agrarian area, the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon was self-sustaining even during the deprivations of the war. Although hunger was widespread, there was always enough food to get by. Most children attended either the local public school run by Roger Darcissac, or The New Cévenole School. Young adults went to farm and trade schools. During free time, various activities were organized. Winter sports were very popular, especially because of the long winter. In the summer, the children played an assortment of sports and swam in the Lignon River.

While Jews were relatively safe in the villages, the gendarmes (armed police) attempted periodic raids. August Bohny, the head of the Swiss Red Cross in Le Chambon, once sent the gendarmes away claiming that they were on Swiss property, forcing them to return to Le Puy-en-Velay to verify the claim. Bohny thus had time to send the Jewish children into the forest. When the gendarmes returned, there were only Protestant children in the homes, and the police left without making arrests.

Image: The children of La Guespy in the snow. Victor Lucien Zinger is the boy winking with blond hair.Credit: Private collection of Victor Lucien Zinger

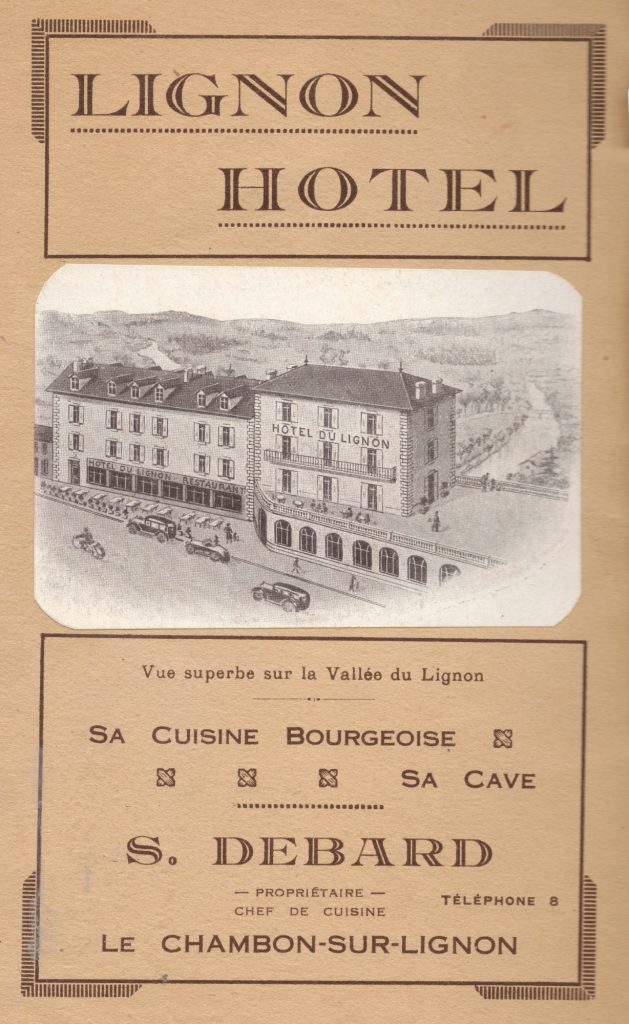

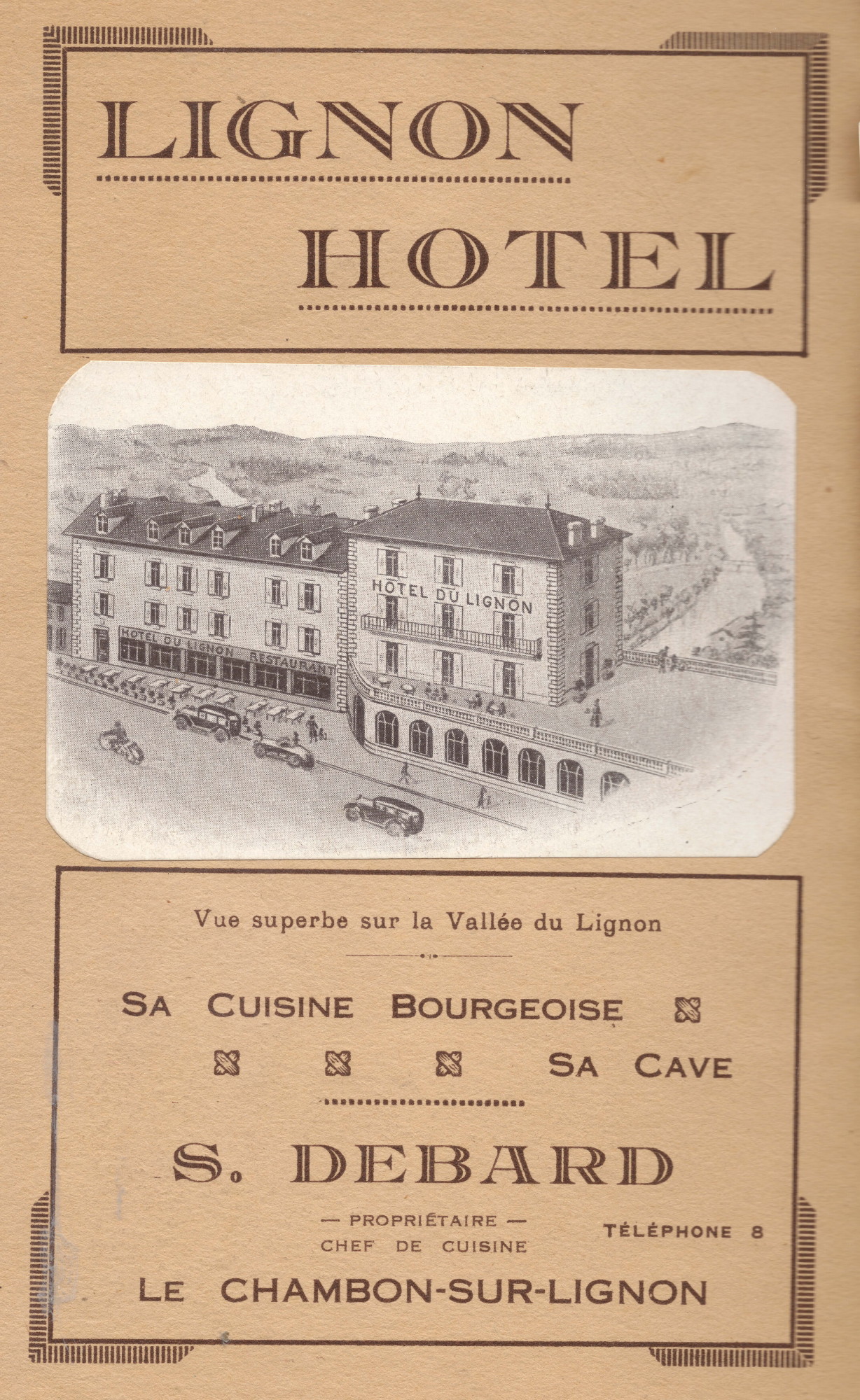

Hôtel du Lignon

1942

In December 1942, the Hôtel du Lignon was requisitioned by the Germans to use as a convalescence home for soldiers returning from the Russian front. This put Nazis in the center of town, but that did not stop the locals from continuing to help refugees.

Image: An advertisement for the Hôtel du LignonCredit: Commune du Chambon-sur-Lignon

Hanne and Max deport from Gurs

The Œuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE) “transferred” Hanne and Max from Gurs. Hanne immediately went to Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, but Max went to Taluyers, near Lyon, where he was denied false papers. Max then fled to Le Chambon, hid for three weeks, and was given papers stating he was an Alsatian named “Charles Lang.” He then escaped to Switzerland.

Hanne and Max deport from Gurs

1942

The Œuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE) “transferred” Hanne and Max from Gurs. Hanne immediately went to Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, but Max went to Taluyers, near Lyon, where he was denied false papers. Max then fled to Le Chambon, hid for three weeks, and was given papers stating he was an Alsatian named “Charles Lang.” He then escaped to Switzerland.

Image: Operation Bürckel, when Jews in the Saar, Palatinate, and Baden regions were arrested and deported to GursCredit: Stadtarchiv Mannheim

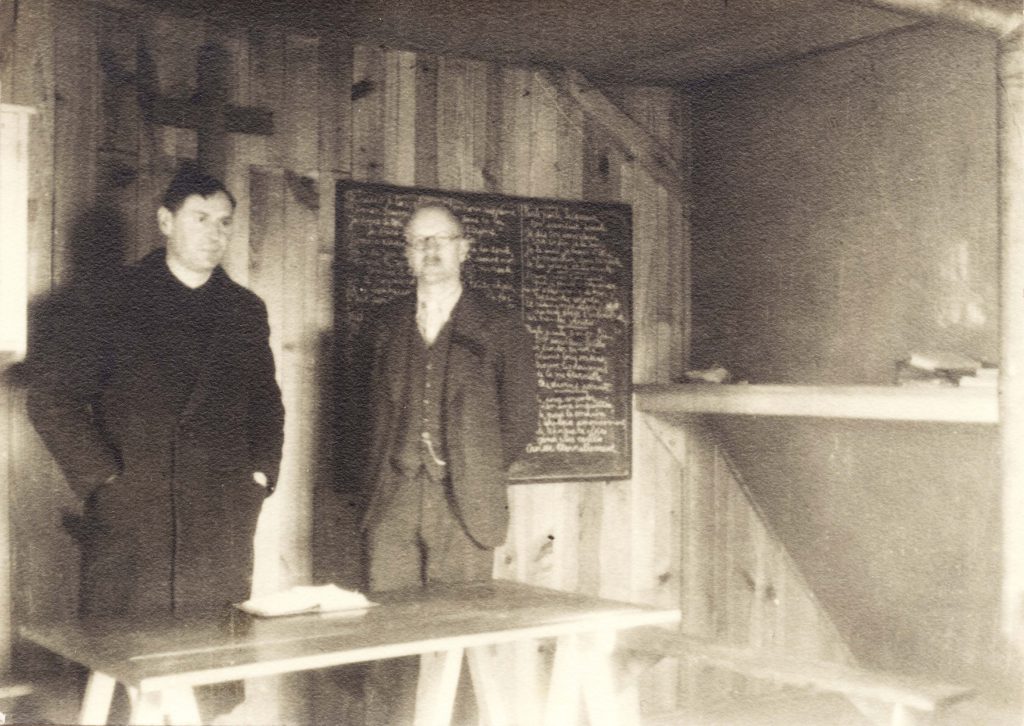

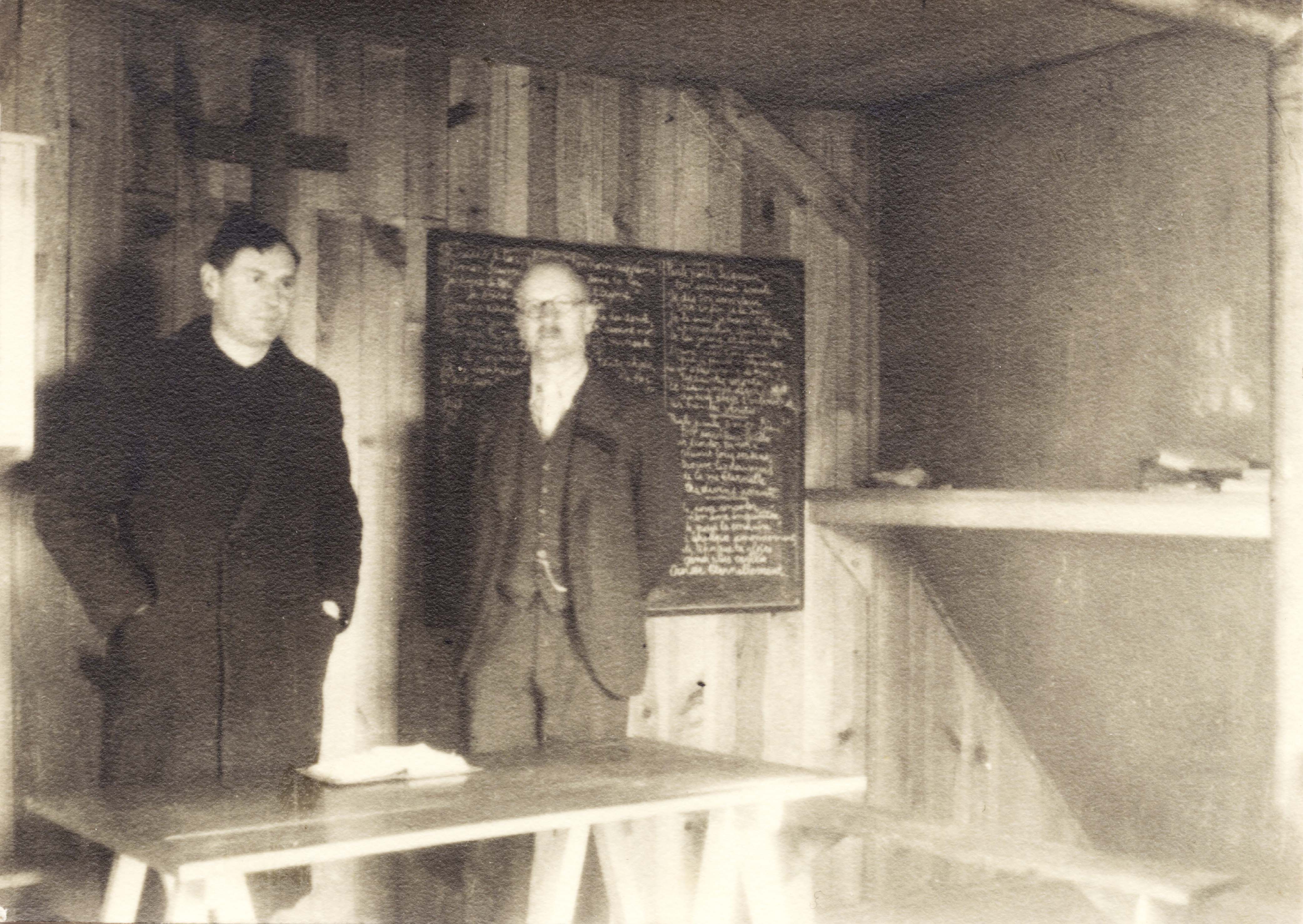

Raid on La Maison des Roches

La Maison des Roches (The House of Rocks) was a residence for older students in their early 20s. Early on June 29, 1943, the Gestapo arrived and arrested eighteen young men, along with their teacher, Daniel Trocmé, Pastor Trocmé’s cousin. Seven non-Jews survived, but Daniel Trocmé died in the Majdanek concentration camp. This was the only mass arrest ever to take place on the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon.

This is a testimony from a student of Daniel Trocmé, Peter Feigel:

Raid on La Maison des Roches

1943

La Maison des Roches (The House of Rocks) was a residence for older students in their early 20s. Early on June 29, 1943, the Gestapo arrived and arrested eighteen young men, along with their teacher, Daniel Trocmé, Pastor Trocmé’s cousin. Seven non-Jews survived, but Daniel Trocmé died in the Majdanek concentration camp. This was the only mass arrest ever to take place on the Plateau Vivarais-Lignon.

This is a testimony from a student of Daniel Trocmé, Peter Feigel:

Credit: Photo taken by Paul Kutner, 2017

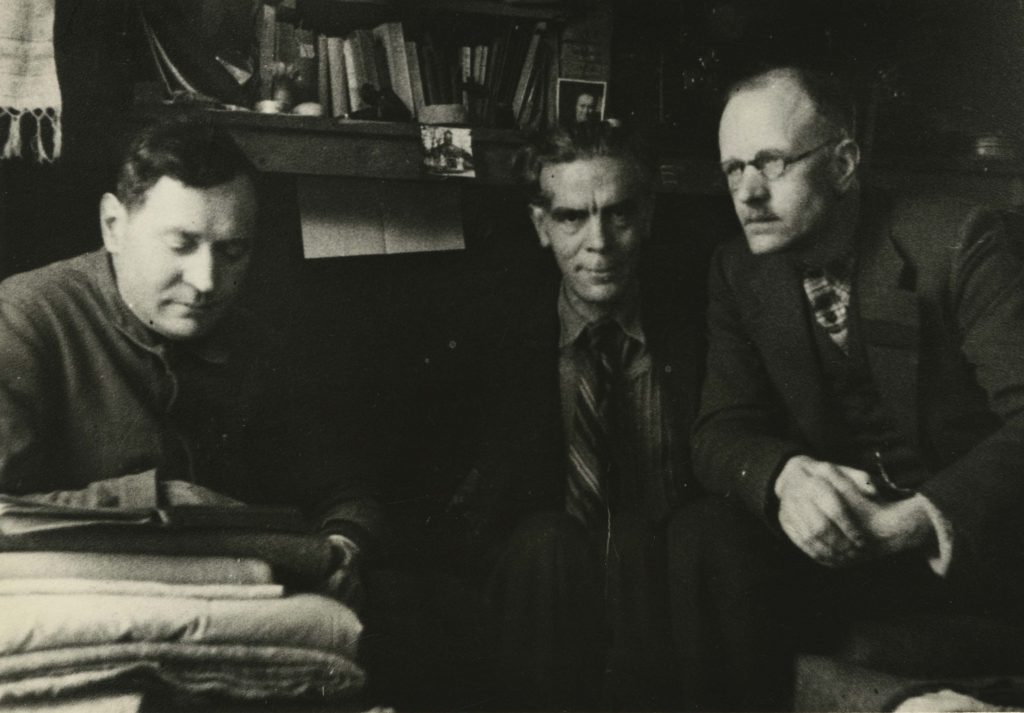

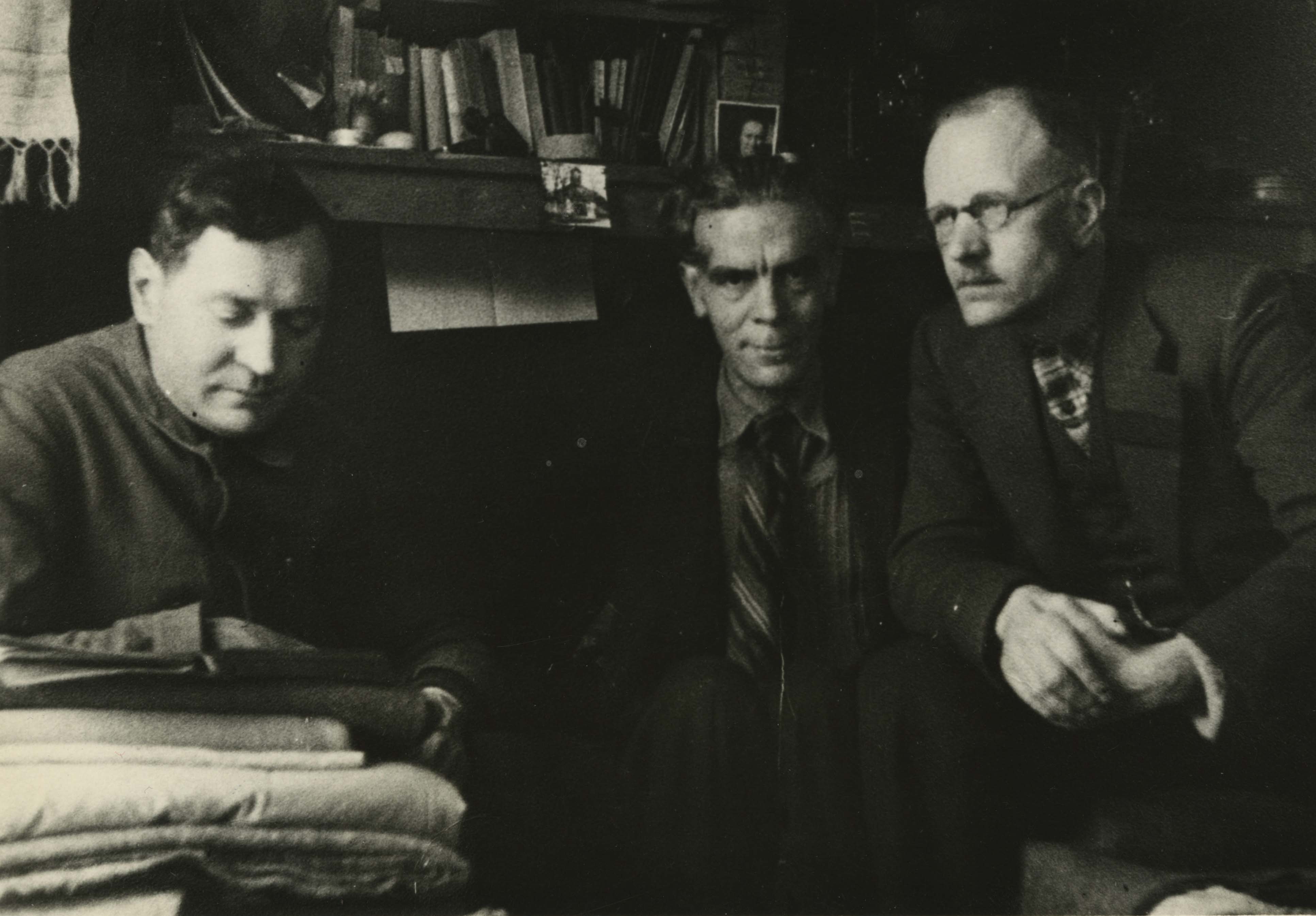

Leaders of the Conspiracy Arrested

As the size and scope of the rescue on the Plateau grew, French police arrested Pastors Trocmé and Theis, as well as school director Roger Darcissac, on February 13, 1943, and charged them with breaking Vichy laws. Held at Saint-Paul d’Eyjeaux, an internment camp near Limoges, they were released once Pastor Bœgner intervened. Although Darcissac was forced to sign a pledge of allegiance to the Vichy regime, the pastors refused, since to do so would be to bear false witness. They were released nevertheless.

Leaders of the Conspiracy Arrested

1943

As the size and scope of the rescue on the Plateau grew, French police arrested Pastors Trocmé and Theis, as well as school director Roger Darcissac, on February 13, 1943, and charged them with breaking Vichy laws. Held at Saint-Paul d’Eyjeaux, an internment camp near Limoges, they were released once Pastor Bœgner intervened. Although Darcissac was forced to sign a pledge of allegiance to the Vichy regime, the pastors refused, since to do so would be to bear false witness. They were released nevertheless.

Image: Pastor Édouard Theis, Roger Darcissac, & Pastor André Trocmé interned at Saint-Paul d’EyjeauxCredit: André Trocmé and Magda Trocmé Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection

Pastors in Exile

Pressure from the Resistance and the Reformed Church of France forced Pastors Trocmé and Theis into exile from July 1943 until the Liberation in 1944. According to a Resistance double-agent, the Gestapo had put a price on the pastors’ heads, and the Reformed Church did not want any further trouble that might endanger the town, especially after Daniel Trocmé’s arrest.

Pastors in Exile

1943

Pressure from the Resistance and the Reformed Church of France forced Pastors Trocmé and Theis into exile from July 1943 until the Liberation in 1944. According to a Resistance double-agent, the Gestapo had put a price on the pastors’ heads, and the Reformed Church did not want any further trouble that might endanger the town, especially after Daniel Trocmé’s arrest.

Image: Pastors Theis and Trocmé interned at St. Paul d’EyjeauxCredit: André Trocmé and Magda Trocmé Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection

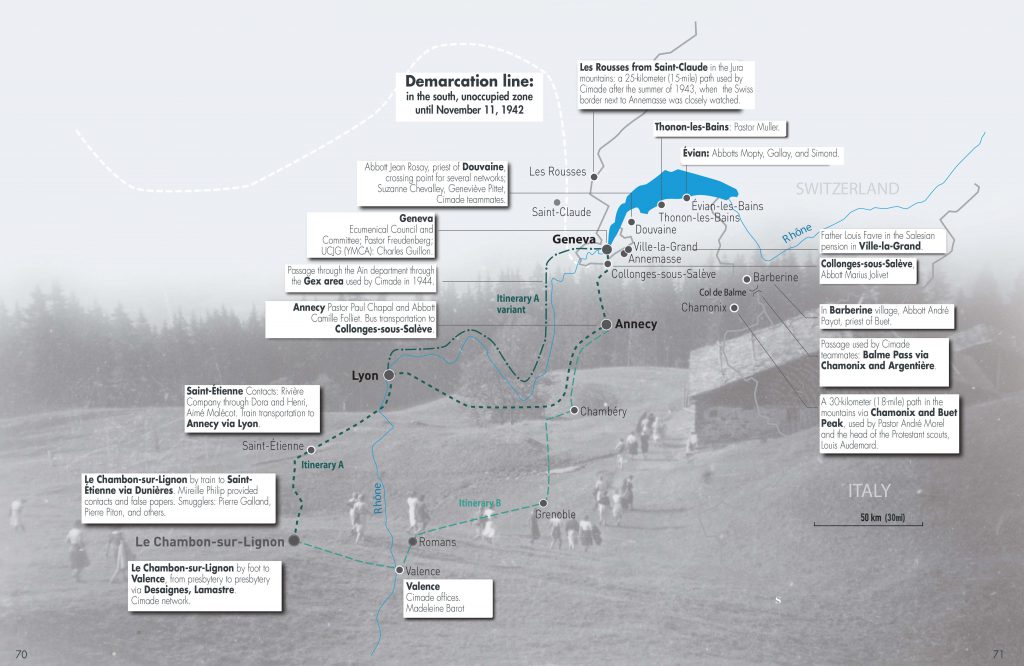

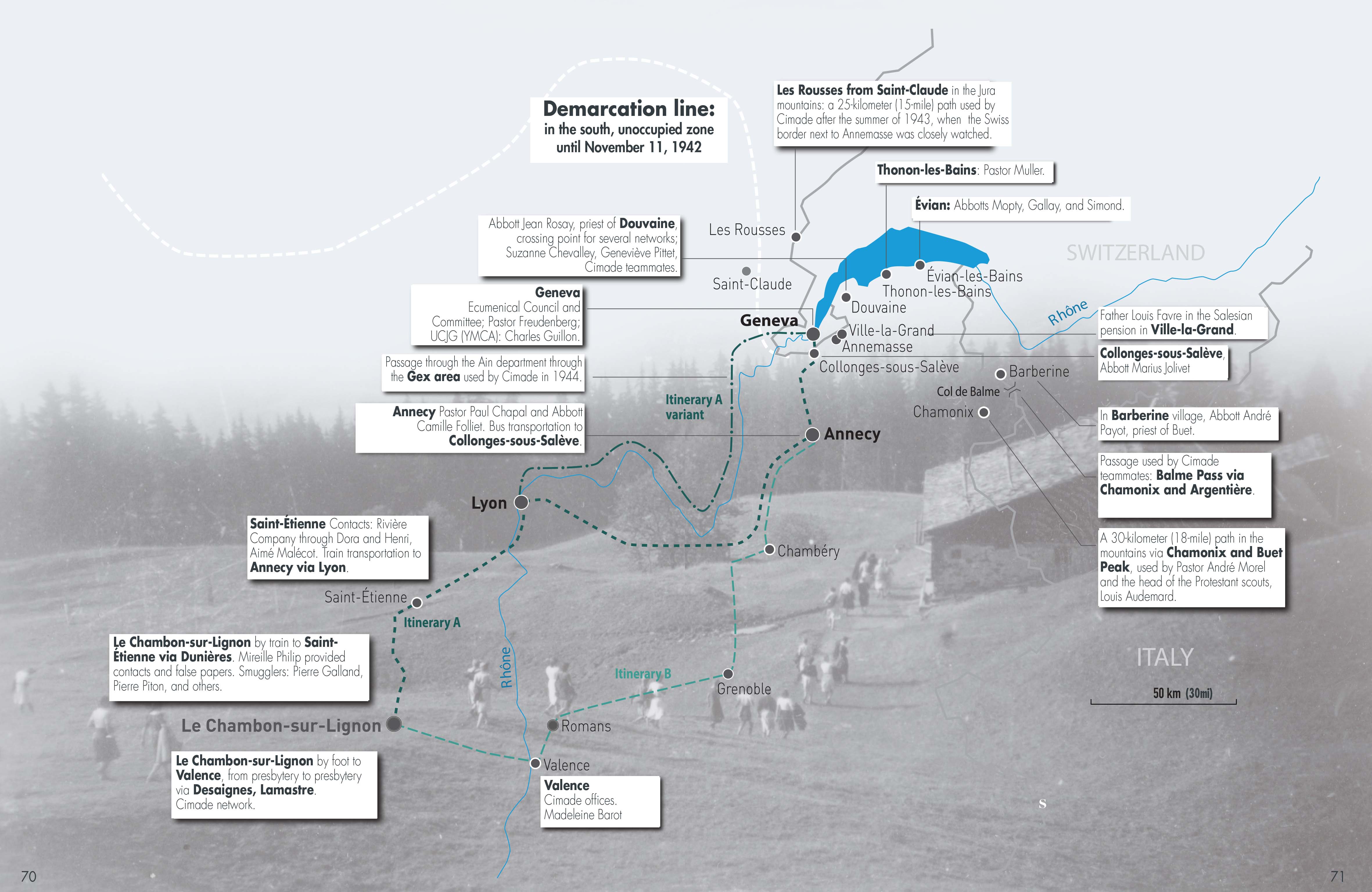

False Documents and Escape

Due to local raids and constant anxiety, many of the Jews hiding on the Plateau were eager to escape. With the help of Pastor Marc Bœgner, the president of the Reformed Church of France, the Œuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE), the Cimade, and the Amitié Chrétienne (Christian Friendship), a network was put in place to bring refugees to Switzerland, some 300 kilometers away. Many of the contacts along the way were Catholic priests or Protestant ministers.

Fake identity cards proved essential in smuggling Jews out of France. The Plateau had several forgers at work making false documents, including: Pastor Theis and Mireille Philip; Aimé Malécot, who was also one of the transporters of refugees; and a Jewish refugee, Oscar Rosowsky, who made about 50 false papers per week and hid his forgery equipment in beehives. One smuggler, Pierre Piton, was arrested after several missions, but was ultimately released by Italian fascist police.

One Kupferberg Holocaust Center volunteer escaped to Switzerland using false papers that described her as “Anne-Marie Husser,” of Paris, whose true identity was Johanna Hirsch from Karlsruhe, Germany.

False Documents and Escape

1941-1944

Due to local raids and constant anxiety, many of the Jews hiding on the Plateau were eager to escape. With the help of Pastor Marc Bœgner, the president of the Reformed Church of France, the Œuvre de Secours aux Enfants (OSE), the Cimade, and the Amitié Chrétienne (Christian Friendship), a network was put in place to bring refugees to Switzerland, some 300 kilometers away. Many of the contacts along the way were Catholic priests or Protestant ministers.

Fake identity cards proved essential in smuggling Jews out of France. The Plateau had several forgers at work making false documents, including: Pastor Theis and Mireille Philip; Aimé Malécot, who was also one of the transporters of refugees; and a Jewish refugee, Oscar Rosowsky, who made about 50 false papers per week and hid his forgery equipment in beehives. One smuggler, Pierre Piton, was arrested after several missions, but was ultimately released by Italian fascist police.

One Kupferberg Holocaust Center volunteer escaped to Switzerland using false papers that described her as “Anne-Marie Husser,” of Paris, whose true identity was Johanna Hirsch from Karlsruhe, Germany.

Image: The various escape routes from villages on the Plateau to Switzerland.Credit: Lieu de Mémoire

Resistance and Liberation

Throughout the Plateau, pastors called for resistance to Vichy’s anti-Jewish laws. Pastor André Bettex of nearby Le Mazet-St. Voy, declared, “The measures taken against the Jews are illegal. Conscience can only revolt around such measures. Our duty is to rescue them, hide them, and to save them by every means possible. I enlist you to do this.” Similarly, Pastor Roland Leenhardt of Tence declared, “Jews are being terrorized by the French…We must fight against the measures taken against the Jews.”

Major Protestant and Catholic clergy—such as Pastor Marc Bœgner, President of the Reformed Church of France, and Cardinal Jules Saliège, Archbishop of Toulouse—also denounced roundups of Jews.

The Protestant churches on the Plateau were the organizational and motivational leaders of the efforts to rescue refugees and resist collaboration or complicity with the Vichy regime. Sunday services were packed and sermons promoted unity, morality, and unwavering faith in the righteousness of their effort.

Resistance and Liberation

1942-1944

Throughout the Plateau, pastors called for resistance to Vichy’s anti-Jewish laws. Pastor André Bettex of nearby Le Mazet-St. Voy, declared, “The measures taken against the Jews are illegal. Conscience can only revolt around such measures. Our duty is to rescue them, hide them, and to save them by every means possible. I enlist you to do this.” Similarly, Pastor Roland Leenhardt of Tence declared, “Jews are being terrorized by the French…We must fight against the measures taken against the Jews.”

Major Protestant and Catholic clergy—such as Pastor Marc Bœgner, President of the Reformed Church of France, and Cardinal Jules Saliège, Archbishop of Toulouse—also denounced roundups of Jews.

The Protestant churches on the Plateau were the organizational and motivational leaders of the efforts to rescue refugees and resist collaboration or complicity with the Vichy regime. Sunday services were packed and sermons promoted unity, morality, and unwavering faith in the righteousness of their effort.

Image: Celebrating the Liberation on May 8, 1945, at the town hall of Le Chambon-sur-LignonCredit: Fonds August Bohny, Archiv für Zeitgeschichte, Zürich

Hanne and Max Get Married

1945

Hanne and Max Liebmann were married on April 14, 1945, and went on to have one daughter, one grandson and two great-granddaughters. They recently celebrated their 72nd wedding anniversary.

Image: Hanne and Max Liebmann in their home in Queens, NY, 2017Credit: Private collection of Hanne and Max Liebmann

Pastor Trocmé Recognized by Yad Vashem Museum as Righteous Among the Nations

One of the most enduring lessons of Le Chambon is the humility and sincerity with which the villagers approached their heroic rescue of the refugees who arrived on their doorstep. When he received Yad Vashem’s Righteous Among the Nations designation in 1971, Pastor Trocmé said:

Why me and not the host of humble peasants of the Haute-Loire, who did as much and more than I did? Why not my wife, whose actions were much more heroic than mine? Why not my colleague Edouard Theis, with whom I shared all responsibilities? I can accept the ‘Medal of the Righteous’ only on behalf of all those who took risks to save our brothers and sisters who were unjustly persecuted with death.

Pastor Trocmé Recognized by Yad Vashem Museum as Righteous Among the Nations

1971

One of the most enduring lessons of Le Chambon is the humility and sincerity with which the villagers approached their heroic rescue of the refugees who arrived on their doorstep. When he received Yad Vashem’s Righteous Among the Nations designation in 1971, Pastor Trocmé said:

Why me and not the host of humble peasants of the Haute-Loire, who did as much and more than I did? Why not my wife, whose actions were much more heroic than mine? Why not my colleague Edouard Theis, with whom I shared all responsibilities? I can accept the ‘Medal of the Righteous’ only on behalf of all those who took risks to save our brothers and sisters who were unjustly persecuted with death.

Image: Pastor André Trocmé

Credit: André Trocmé and Magda Trocmé Papers, Swarthmore College Peace Collection

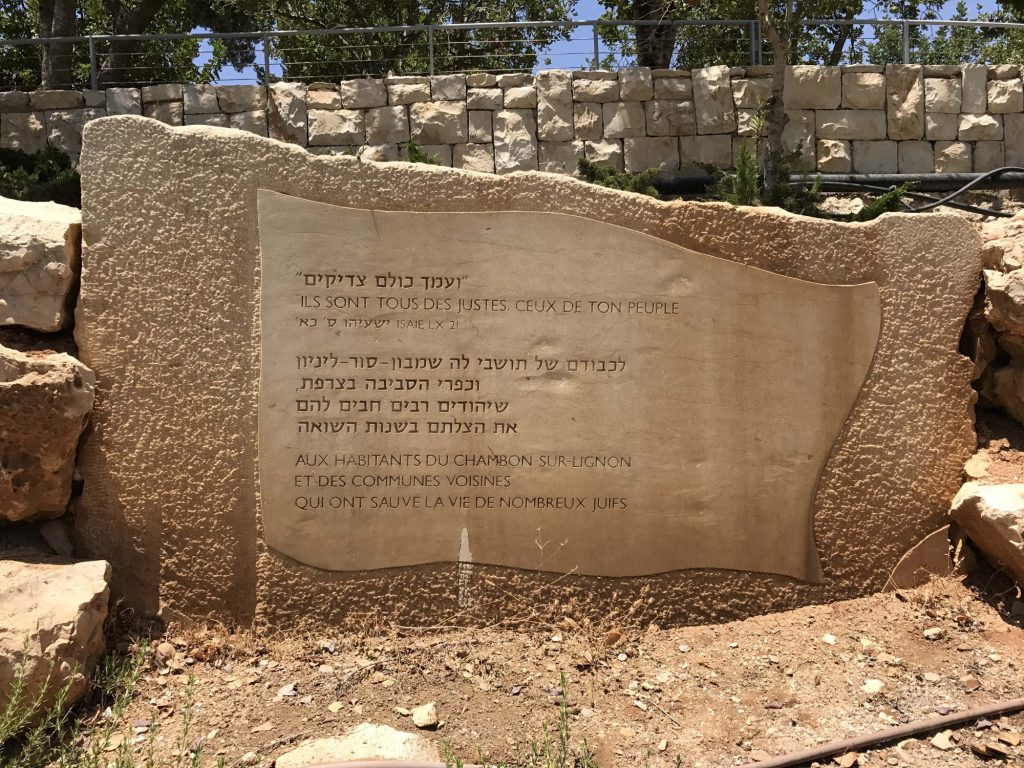

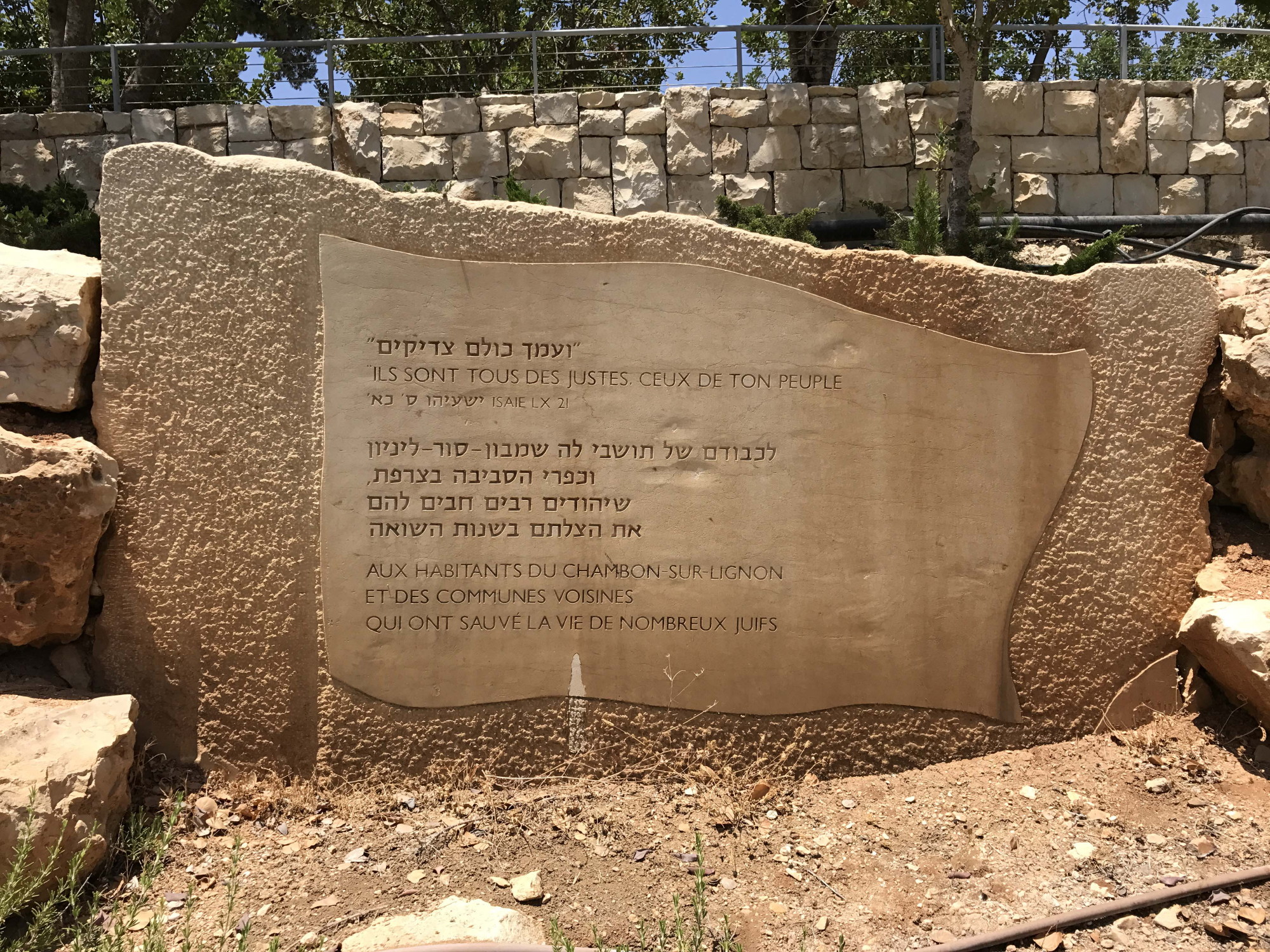

Rescuers in the Plateau Recognized by Yad Vashem Museum as Righteous Among the Nations

Many more medals were issued in the years that followed and are still being issued, posthumously, to residents of the Plateau. They have all been awarded the Medal of the Righteous, Israel’s highest civilian honor, inscribed with these words from the Talmud, “Whoever saves a life has saved the entire world.” Additionally, in 1979, a plaque was placed in the village across the street from the Protestant church inscribed with a Biblical quote, “The memory of the Righteous will remain forever” (Psalms 112:6).

Rescuers in the Plateau Recognized by Yad Vashem Museum as Righteous Among the Nations

1979

Many more medals were issued in the years that followed and are still being issued, posthumously, to residents of the Plateau. They have all been awarded the Medal of the Righteous, Israel’s highest civilian honor, inscribed with these words from the Talmud, “Whoever saves a life has saved the entire world.” Additionally, in 1979, a plaque was placed in the village across the street from the Protestant church inscribed with a Biblical quote, “The memory of the Righteous will remain forever” (Psalms 112:6).

Credit: Photo taken by Paul Kutner, 2017

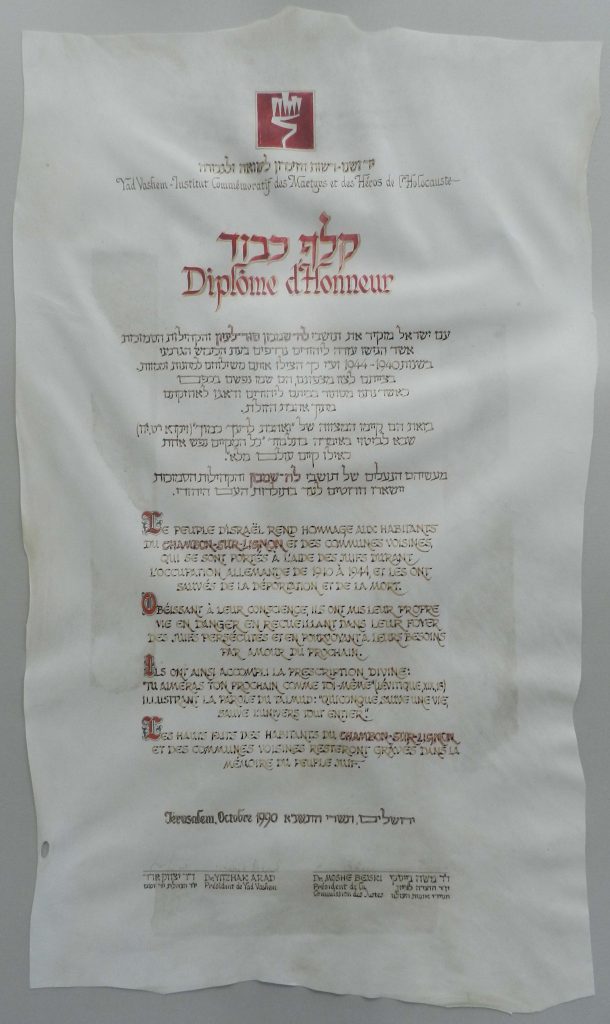

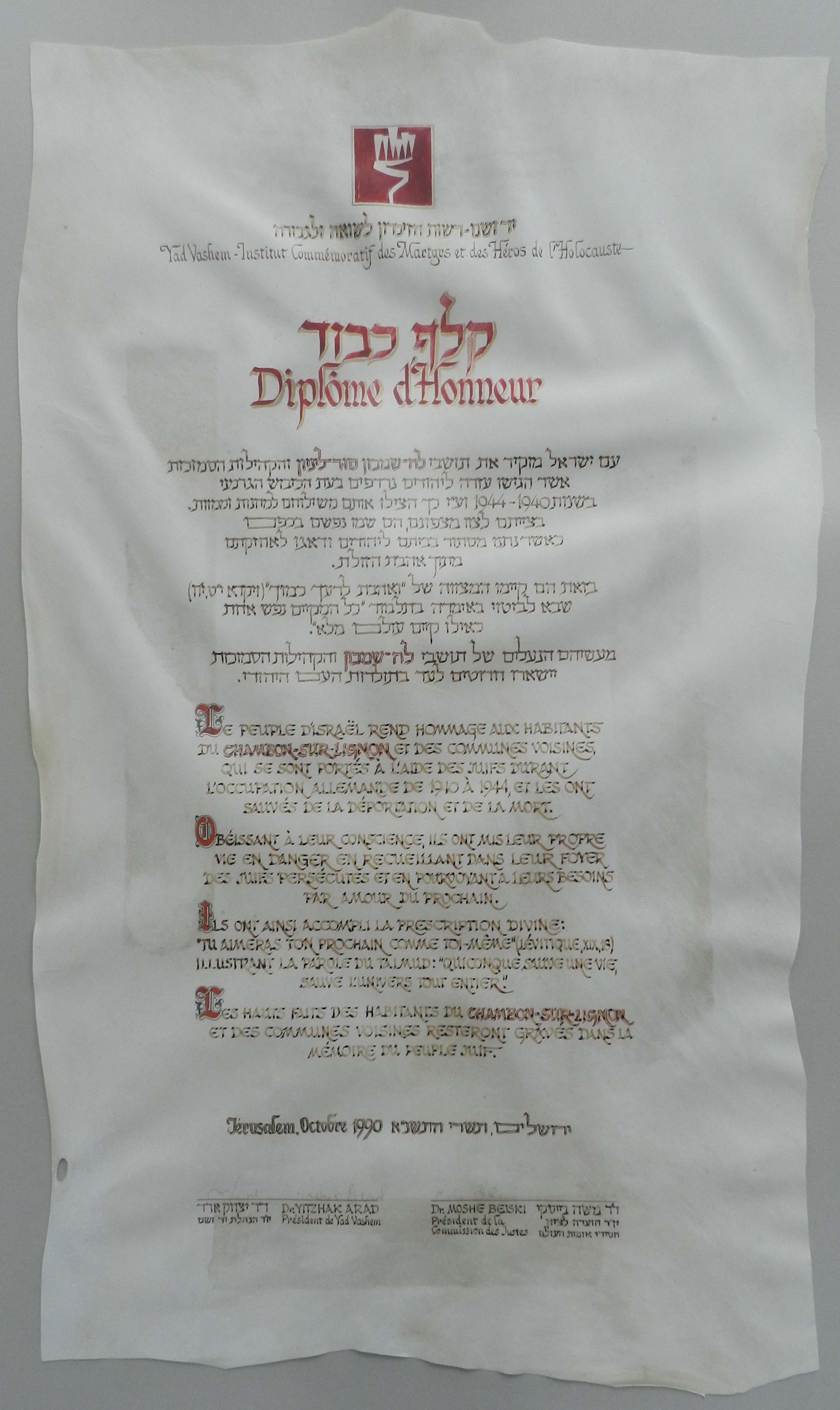

Le Chambon and the Plateau Honored by Yad Vashem Museum

Trocmé’s remarks launched a campaign by rescued Jews to have Yad Vashem, Israel’s national Holocaust memorial, recognize the broader rescue on the Plateau. This effort was joined by Hanne and Max Liebmann, who worked tirelessly alongside other former refugees, and ultimately succeeded in 1988 when Yad Vashem’s Department of the Righteous issued a special Diplôme d’Honneur. This honor recognized the residents of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and the surrounding villages for “coming to the aide of Jews during the German Occupation,” for “obeying their conscience,” and for “accomplishing the divine instruction ‘You will love your neighbor as yourself.’”

Le Chambon and the Plateau Honored by Yad Vashem Museum

1988

Trocmé’s remarks launched a campaign by rescued Jews to have Yad Vashem, Israel’s national Holocaust memorial, recognize the broader rescue on the Plateau. This effort was joined by Hanne and Max Liebmann, who worked tirelessly alongside other former refugees, and ultimately succeeded in 1988 when Yad Vashem’s Department of the Righteous issued a special Diplôme d’Honneur. This honor recognized the residents of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and the surrounding villages for “coming to the aide of Jews during the German Occupation,” for “obeying their conscience,” and for “accomplishing the divine instruction ‘You will love your neighbor as yourself.’”

Image: The special certificate issued to Le Chambon-sur-Lignon and the neighboring villages by Yad Vashem Holocaust Institute, displayed in the Memorial Museum of Le Chambon-sur-LignonCredit: Lieu de Mémoire

Marie Brottes Reflects on Le Chambon

In 1996, Marie Brottes, one of the Righteous of Le Chambon, wrote the following to Yad Vashem Holocaust Institute in Jerusalem:

“It has already been fifty years since, in great secret, here on the Plateau in the Haute-Loire, we shared our bread and gave asylum to these destitute people. We did not do it for a certificate, nor for a medal, nor for a tree in the Garden of the Righteous! We simply applied God’s word according to Isaiah 58:7. How glorious it is to help one’s neighbor.”

Marie Brottes Reflects on Le Chambon

1996

In 1996, Marie Brottes, one of the Righteous of Le Chambon, wrote the following to Yad Vashem Holocaust Institute in Jerusalem:

“It has already been fifty years since, in great secret, here on the Plateau in the Haute-Loire, we shared our bread and gave asylum to these destitute people. We did not do it for a certificate, nor for a medal, nor for a tree in the Garden of the Righteous! We simply applied God’s word according to Isaiah 58:7. How glorious it is to help one’s neighbor.”

Image: Marie Brottes, a Darbyist who hid a Jewish family in Le Chambon, recognized in 1989 by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the NationsCredit: Yad Vashem Holocaust Institute, Jerusalem